Jeff Erenstone, CPO, chief designer of Performance Orthotic Design and president and head clinician of Mountain Orthotic & Prosthetic Services, both located in Lake Placid, New York, specializes in crafting personalized adaptive sports equipment

from his office at the site of the 1980 Winter Olympics. Recently, he built a cross-country sit-ski that will be used by Dan Cnossen in the 2014 Paralympic Winter Games in Sochi, Russia. The O&P EDGE asked Erenstone to describe the process of developing Cnossen’s sit-ski.

Cnossen, an active-duty lieutenant commander and Navy SEAL, stepped on an improvised explosive device in 2009 during his service in Afghanistan, resulting in serious injuries that included bilateral transfemoral amputations. Leading up to the Winter Games, Cnossen took four medals at the January 2013 International Paralympic Committee Nordic Skiing World Cup in Cable,

Wisconsin-two in cross-country skiing and two in biathlon, leading the U.S. Paralympics to call him “the top U.S. contender in cross-country heading into Sochi.”

“These are top athletes,” Erenstone says about those for whom he designs adaptive equipment. “They just have a missing limb.”

Dan Cnossen. Photograph courtesy of James Netz Photography.

The first rule of adaptive sports design is that it will not work the first time, so expect to make it at least twice. My first step, before I started anything, was to talk to Cnossen about what he needed and wanted in a sit-ski. Then I watched him ski.

Athletes think about their equipment all the time-

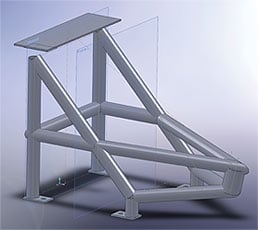

what it does well, what it could do better. For example, Cnossen knows that the more vertical his leg position is, the more weight he can shift forward and the more force he can put on the poles for propulsion. Sit-ski devices typically have a near-level position or slight downward tilt of the athlete’s lower body. The steepest angle that had been achieved was 30 degrees; Cnossen wanted to be in the 40-degree range. Because his prosthetic sockets are designed to bear weight, I suggested we use the same technology for a prosthetic/sit-ski hybrid. Before I built the first prototype, we removed the sockets from his prostheses and tried to perfect the height and angles of his position in the sit-ski by piling up books around him for support.

From that, I created a CAD/CAM sketch of the assembly from which I could build a proof of concept.

I always put a lot of time and effort into building a proof of concept, and then build and test prototypes,

before having the finished product fabricated. My proof-of-concept devices are made of wood, plastic, metal-whatever is available. It’s important not to spend a lot of time and money on a concept until you know that it works. In this case, I wanted to make sure that the seat angle was correct before making an expensive, professionally welded device.

I used the designs in Figures 1-3 to build the first prototype in 2012. After testing, the single attachment point in the front proved to be too flexible, so I reconfigured the design. In late 2013, after testing several more prototypes, I showed a revised version of the CAD/CAM design to engineers from Johns Hopkins

University, Baltimore, Maryland, and they recommended that I remove a bar I had at the bottom and instead build a posterior ledge that would attach the seat and leg forms to the frame. I realized how obvious their suggestion was as soon as I heard it. I had originally used the bar to allow for adjusting the

angle of Cnossen’s position on the device, but since I had tested the angles for a year and knew they were right, the new version would provide significant weight savings.

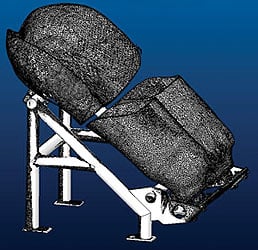

Figure 1. Photographs and images courtesy of Jeff Erenstone, unless otherwise stated.

Figure 3

Figure 4

Figure 2

Figure 5

Cnossen and I spent two weeks in the off-season testing

and prototyping three more versions of the device, which we secured to a mountain board (Figures 4 and 5).

When we tested the device on the mountain board the first time, we found that there was too much slope in the single mount for the two sockets. We had a new socket support welded to the outside of the leg, and the sockets could then be mounted to a carbon plate on the support.

When building these kinds of specialized devices, it is best to get a functional and reliable device and then stop. During the season, an athlete should focus on training, not testing revisions. Improvements can be made in the next off-season. Our goal for next year will be to see if we can decrease the weight of Cnossen’s sit-ski, which will enable him to increase his speed.

“[A custom sit-ski is] a really important part of the sport; you have to be comfortable, you have to be well secured…not only for power transfer, but for ski control,” Cnossen told Faster Skier magazine when discussing his Paralympic chances. “I know I’m stronger physically this year and I have better equipment, so it will be exciting to see how I end up on the results list.”