The 2008 movie Kung Fu Panda tells the story of a young panda named Po who is obsessed with becoming a kung fu master. He works for his restaurateur father, whose specialty is a soup that contains a secret ingredient, and feels pressure to pursue the more reasonable goal of someday taking over the family business. Against all odds, he is selected to train to become the Dragon Warrior and defend the Valley of Peace from the villainous Tai Lung. Po begins rigorous training in hopes of achieving the skills necessary to be worthy to read the Dragon Scroll, which contains the secret to limitless power. As the training progresses, Po’s feelings of inadequacy persist, and he remains convinced that he will never be skilled enough to defeat Tai Lung. This belief is shared by other kung fu masters he is training with, one of whom tells him, “You don’t belong here.” At one point Po says to his trainer, “There’s no way I’m ever gonna be like you!”1

Many trainees in health disciplines experience similar self-doubt when navigating the challenges of a rigorous clinical program. Possessing minimal practical experience, many feel like a fraud when completing clinical tasks, especially after leaving the relatively low-stakes education environment and interacting with patients in real-world clinical settings. These feelings are common among the highest performing students and trainees and often do not diminish later in their careers as they gain the experience, clinical success, and professional credentials that validate their expertise. This reality, first labelled as imposter phenomenon (IP) and commonly referred to as imposter syndrome (IS), “often overlaps with anxiety, depression, stress, and burnout.”2

Early Observations

In 1978 clinical psychologists Pauline Clance, PhD, ABPP, and Suzanne Imes, PhD, published a report identifying the imposter phenomenon they had observed while working with more than 150 highly successful women during a five-year period.3 Their sample included “primarily white middle- to upper-class women between the ages of 20 and 45” who were undergraduate students, doctoral faculty members, medical students and “professional women in such fields as law, anthropology, nursing, counseling, religious education, social work, occupational therapy, and teaching.”3 Clance and Imes found that “despite outstanding academic and professional accomplishments, women who experience the imposter phenomenon persist in believing that they are really not bright and have fooled anyone who thinks otherwise.”3 Despite the significant success these women had achieved, they found “innumerable means of negating any external evidence that contradicts their belief that they are, in reality, unintelligent.”3 They expressed “fear that eventually some significant person will discover that they are indeed intellectual imposters.”3 Like Po the panda, these women continued to doubt their abilities even after significant achievements and external validation of their abilities.

Attribution Theory

As confirmation of their observations, Clance and Imes cited attribution theorists who have studied the different expectations of men and women related to “their ability to perform successfully on a wide variety of tasks,” and the factors to which they attribute their success.3 They describe how “an unexpected performance outcome will be attributed to a temporary cause…. An expected performance outcome will be attributed to a stable cause.”3 They explain that “in line with their lower expectancies, women tend to attribute their successes to temporary causes, such as luck or effort, in contrast to men who are much more likely to attribute their successes to the internal, stable factor of ability. Conversely, women tend to explain failure with lack of ability, whereas men more often attribute failure to luck or task difficulty.”3

Counter to the assumption that “repeated success experiences over a period of time should begin to change one’s expectancies,” Clance and Imes reported being “amazed at the self-perpetuating nature of the imposter phenomenon—with the pervasiveness and longevity of the imposter feelings of our high-achieving women, with their continual discounting of their own abilities and persistent fear of failure. We have not found repeated successes alone sufficient to break the cycle.”3 High academic and professional performance does not provide sufficient evidence to counter the belief that one is an imposter, and instead this success is interpreted through the lens of that self-identification.

Origins of the Imposter Phenomenon

Based on their experience working with these women, Clance and Imes identified two family histories that contribute to the development of the IP. In some cases, a sibling or close relative was “designated as the ‘intelligent’ member of the family” while the one with IP “has been told directly or indirectly that she is the ‘sensitive’ or socially adept one in the family.”3 The individual may feel compelled to prove her intellect and abilities only to find that the family continues to consider the sibling who has been labelled “bright” as more intelligent, even when that sibling’s academic performance is poorer. In other cases, the one with IP is labelled as having superior “intellect, personality, appearance, and talents” and receives the message that “there is nothing that she cannot do if she wants to, and she can do it with ease.”3 When she begins to encounter challenges that demonstrate her inability and realizes she cannot fulfill the expectations her family has of her, and because she has been “indiscriminately praised for everything, she begins to distrust her parents’ perceptions of her” and “begins to doubt herself.”3 According to Clance and Imes, “having internalized her parents’ definition of brightness as ‘perfection with ease,’ and realizing that she cannot live up to this standard, she jumps to the conclusion that she must be dumb.”3

Clance and Imes described the relationship between family and societal factors as “a chicken or egg problem” and concluded based on their experience that “the imposter phenomenon begins to develop originally in both groups of girls in relation to the family” and that “societal sex-role stereotyping…can be transmitted through the parents.”3 They describe a dynamic in which “the girls in the ‘sensitive’ group appear to develop their original self-doubts about their intellect from the differential between their perception that they are not considered bright and their actual high achievements.”3 Girls labelled as ‘bright,’ on the other hand, “first develop self-doubts from the small differential between what they are expected to achieve and what they can achieve.”3

Maintaining the Imposter Phenomenon

Clance and Imes reported that self-identification as an imposter is reinforced by several behaviors. The supposed imposters may work hard to prevent discovery of their fraud. When their hard work results in success they experience temporary feelings of competence. However, the imposter “develops an unstated…belief that if she were to think she could succeed she would actually fail” and “the underlying sense of phoniness remains untouched.”3 Imposters may also “engage in intellectual inauthenticity” by not expressing their ideas or opinions, intellectually flattering authority figures, and not expressing opposing viewpoints.3 Since this behavior does not allow their opinions and perspectives to be demonstrated as correct or valuable, it serves to support their self-assessment as imposters. An imposter may use “charm and perceptiveness to win approval of superiors” with the aim of being “liked as well as to be recognized as intellectually special.”3 The imposter then questions whether the affirmations of her abilities are based on those other attributes and “to believe that if she were really bright she would not need outside approval.”3 Finally, understanding that “negative consequences that are likely to befall the woman in our society who displays confidence in her ability,” an imposter may “maintain the notion that she is not bright” to “avoid social rejection.”3

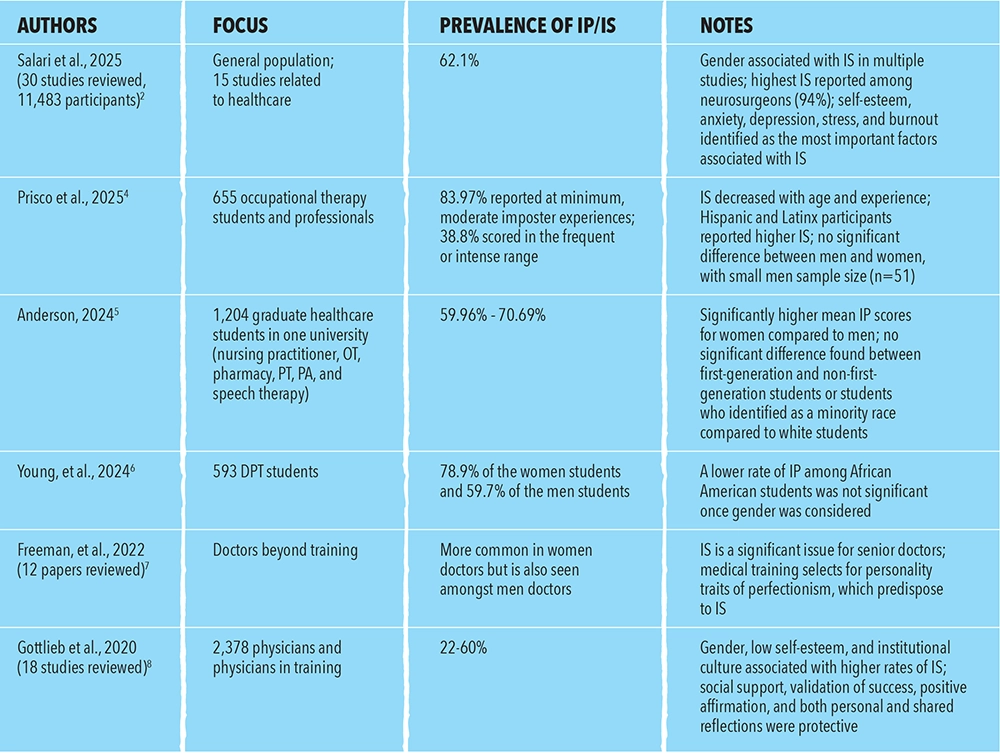

While societal expectations have changed some in the decades since Clance and Imes published their paper, many students and practitioners can relate to what they observed in their clients. Recent research on the prevalence of the IP in healthcare education and practice has confirmed that while men are not immune from this phenomenon, it occurs more frequently among women. Research also demonstrates that IP persists well beyond the initial training period. (See Table 1.)

While societal expectations have changed some in the decades since Clance and Imes published their paper, many students and practitioners can relate to what they observed in their clients. Recent research on the prevalence of the IP in healthcare education and practice has confirmed that while men are not immune from this phenomenon, it occurs more frequently among women. Research also demonstrates that IP persists well beyond the initial training period. (See Table 1.)

Overcoming the Imposter Phenomenon

Clance and Imes found that multimodal therapy, including group interactions during which other high-achieving women shared their experiences with IP, helped individuals realize that their beliefs are not unique, and group sessions provided the opportunity for imposters to observe the “lack of reality” and negation of positive feedback in other high performers.3 They recommend encouraging a conscious changing of expectation of failure to expectations of success prior to a task to reduce self-doubt and describe small and incremental therapy assignments designed to “practice new ideas about the self as well as to decrease compulsive work habits (which perpetuate ‘effort’ attributions)” as helpful.3 They also recommend that the individual “keep a record of positive feedback she receives about her competence and how she keeps herself from accepting this feedback.”3 Individuals are also encouraged to “risk ‘being herself’ and seeing what happens. Usually, catastrophic expectations do not occur.”3 The authors of a 2024 scoping review of educational interventions for IP reported that in the majority of the 17 reviewed studies (including ten studies targeting healthcare professionals and students) self-reflection and group-guided exercises were the most popular, and “coaching and structured supervision were also suggested.”9

Closing Thoughts

When Po finally obtains the Dragon Scroll that contains the secret to becoming the Dragon Warrior, he sees only his reflection in the shiny surface. It is then that he realizes that his father’s revelation about his noodle soup recipe applies to him: “The secret ingredient is…nothing!” his father had revealed. “To make something special you just have to believe it’s special.” Po states the key lesson of the movie during his confrontation with Tai Lung: “There is no secret ingredient—it’s just you.”

Women now comprise a majority of enrollment in US O&P education programs, and they consistently out-perform their men counterparts in all aspects of training. However, women remain a minority in the profession. This alone can result in questioning whether they belong, a feeling exacerbated by overt and covert messages confirming that suspicion. Pre-existing and deeply entrenched IP can persist as they face the increased demands of clinical education and residency training. Imposters understand that specific knowledge and skills are required to achieve clinical success and added scrutiny based on their gender is likely to reinforce those beliefs and behaviors.

Being aware of the prevalence and patterns of the IP can help educators, clinical mentors, and, most importantly, trainees themselves change this inaccurate self-perception. High standards and expectations can be maintained while addressing IP in a constructive and supportive manner. By describing their own struggles with imposterism, modeling accurate self-assessment, and developing effective feedback skills, supervisors can support their trainees’ confidence in their own performance. Patients depend on the competence and confidence of practitioners who accurately assess their own performance. These clinicians are the secret ingredient in the learning process and effective clinical care.

John T. Brinkmann, MA, CPO/L, FAAOP(D), is an associate professor at Northwestern University Prosthetics-Orthotics Center. He has over 30 years of experience in patient care and education.

References

- https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0441773/plotsummary/

- Salari, N., S. H. Hashemian, and A. Hosseinian-Far, et al. 2025. Global prevalence of imposter syndrome in health service providers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Psychology 13(1):571.

- Clance, P. R., and S. A. Imes. 1978. The imposter phenomenon in high achieving women: Dynamics and therapeutic intervention. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research & Practice 15(3):241.

- Prisco, D., and S. Walsh. 2025. A survey-based quantification of imposter phenomenon in occupational therapy. The Open Journal of Occupational Therapy 13(2):1-15.

- Anderson, S., L. Stephens, and G. Prather, et al.2025. Prevalence of imposter phenomenon in graduate healthcare students.

- Journal of Physical Therapy Education 39(S1):1-172.

- Young. A., K. Handlery, D. Kahl, R. Handlery, and D. James. A survey of the prevalence of imposter phenomenon among us entry-level doctor of physical therapy students. 2024. Journal of Physical Therapy Education 38(1):19-24.

- Freeman, J., and C. Peisah. 2022. Imposter syndrome in doctors beyond training: A narrative review. Australasian Psychiatry 30(1):49-54.

- Gottlieb, M., A. Chung, N. Battaglioli, S. S. Sebok‐Syer, and A. Kalantari. 2020. Imposter syndrome among physicians and physicians in training: A scoping review. Medical Education 54(2):116-24.

- Kamran Siddiqui, Z., H. R. Church, R. Jayasuriya, T. Boddice, and J. Tomlinson. 2024. Educational interventions for imposter phenomenon in healthcare: A scoping review. BMC Medical Education 24(1):43.