Amputees in protective services are

proving that they can effectively serve the public across the

nation as police officers, firefighters, and paramedics–without

limitations. Some amputees originally pursued careers in these

fields, knowing they had something to prove. Others returned to the

line of duty after work-related or other accidents resulted in

amputations. These emergency personnel are paving the way for other

amputees who desire public service positions.

Disability rights advocates currently are helping those who

would like to return to active duty by speaking with attorneys and

equal rights organizations on their behalf. “It’s a timely issue,”

says Morgan Sheets, national campaign director for the Amputee

Coalition of America’s (ACA) Action Plan for People with Limb Loss

(APPLL). “We are currently working with people who were forced into

disability retirement, not allowed to return to work [after

amputations], and one woman who was kicked out of the Police

Academy.” Sheets explains that the ACA, an advocacy organization,

works as a liaison to construct a network of contacts in the

amputee’s local area best suited to help.

Scruggs Fights for Police Career

|

| Karen Scruggs |

The ACA is currently working with 34-year-old Karen Scruggs, who completed six weeks of the nine-week police training at the South Carolina Criminal Justice Academy before the Academy dismissed her. “The [official line] was that I didn’t have good balance because of my missing leg,” she says. “I was harassed through the whole thing and wasn’t even given a chance.”

Scruggs, who stepped on a feed auger on her family’s farm when she was two, has always known that she wanted to help people by becoming a police officer. In 2003, she became the first female above-knee amputee firefighter in the nation, but now finds herself unable to work in the profession she loves. Though she’d like to be on the road to achieving her long-term goal of being promoted to police detective, she’s fighting legal paperwork because she missed her 180-day window to file a complaint with the Americans with

Disability Act (ADA), ACA, or Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC). According to Sheets, people in this situation might have to pursue personal litigation as their only option.

Scruggs recently moved to Georgia with her 14- and

15-year-old children to be near family, where she serves as a

security officer and awaits a decision by the Gainesville Police

Department to hire her. “I love doing the work,” she says. “I want

to let other amputees know that they can still accomplish a

lot.”

Therefore, Scruggs also is the assistant director of the Amputee

Fire Fighters Association (AFFA), established in 2004 to assist

public safety amputees (police officers, paramedics, EMTs, and

firefighters) to return to active duty if they are able to perform

the functions required of the job. “Amputees must be able to do the

same things other [public safety employees] can do,” says National

Director of AFFA David Dunville. “If they can do it, nothing should

stop them from getting their jobs back or from getting this type of

position. They might have to do the job a little differently,

that’s all.”

Firefighter Finds No Welcome

Dunville, a below-knee amputee and avid Mickey Mouse fan, dons a prosthetic leg emblazoned with “Firefighter Mickey.” A major slip and fall in a fire station fractured his distal tibia and fibia above the ankle. After several failed surgical attempts to restore the leg and coping with chronic pain, Dunville made the difficult decision to amputate five inches below the knee in 2003. Soon he will have a new leg designed specifically for firefighters, in which the socket covers the release pin, an important feature that allows another firefighter to grab his leg without causing it to release. However, he has not returned to active duty and blames his department’s desire to find loopholes under ADA guidelines to keep him from returning even to light duty. Though he interviewed for positions, he always was turned down. “Once my leg was amputated, I wasn’t welcomed at the station,” he says. Dunville was forced to take a position at a store he frequented, The Disney Store. “I’m a collector of everything Mickey, so they knew me there and offered me a job where I do the same work everyone else does,” he says.

Because policies vary in departments across the nation, Dunville works to establish a national federal standard, saying, “We need to get lawmakers to sit down with firefighters, EMTs, and makers of prosthetic components. We might find that a lot more are returning to work. We need to show amputee children that they can [aspire] to these jobs, too.” Some of the 112 members of AFFA claim they were turned down for promotions, offered “desk jobs” or light duty only, or have been denied certification. Some fire departments cite the National Fire Protection Act, stating that a prosthesis is not a part of the body and not appropriate fire equipment or gear; therefore amputees can’t be firefighters. “In addition, because three-fourths of the members suffered limb loss when they were off duty, they pay huge amounts for their prostheses,” Dunville says. “It just doesn’t make sense that the government covers [Otto Bock] C-Legs® for military [personnel], but members of law enforcement can’t get one.”

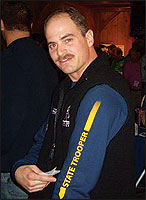

First Amputee NY State Trooper

With the added challenges of a missing limb and possible legal

battles, some are hesitant to return to the field. “Sometimes all

it takes is a broken arm and that’s the straw that breaks the

camel’s back,” explains amputee police trooper Matt Swartz. “They

just get tired of all the bull we deal with on a daily basis and

decide they don’t want to go back.”

But Swartz says he always knew his main goal would be to return

to his job. “It was not a conscious decision, I just wanted to get

back to life as I knew it; get back to being me,” he remembers.

“The conscious decision was more about how do I do that.” Swartz

was thrown from his truck when an oncoming vehicle struck his truck

in 2004. He suffered three skull fractures, causing damage to his

left temporal lobe, brain swelling, and cranial nerve damage. In

addition, his arm was broken and his left leg was crushed. Always a

fighter, Swartz was told later that he struggled with rescuers at

the accident scene. “My survival instinct and training as a cop

made me want to get up, get things done,” he says. “I even tried to

tell the [air rescue] pilot how to fly.” When he awoke six weeks

later from a drug-induced coma, his first memory is of trying to

stand–on one leg. “That’s when I realized they’d had to amputate

my leg, when I fell out of my hospital bed,” he says. “I thought,

leg or no leg, how do I get out of here?'” His wife, who was an

uninjured passenger in the crash, placed his wedding band back on

his finger and told him she’d worn it over her own while he was in

a coma.

He lost his strength those weeks in the hospital, but not his

courage. “The first year was pure determination,” he says. “The

first time I ran outside on my prosthetic leg was July 4, 2005, and

it was a symbol of my freedom.” He gained strength by swimming and

running (Swartz can run a nine-minute mile), even as his bosses

tried to convince him to stay home and take his disability leave.

Every step of the way he photographed and filmed himself doing

various things such as running, climbing a fence, standing in

water, and walking backwards. “I wanted to prove that I am able to

do my job, not disabled or handicapped,” he says. “I thought I’d

have to fight for my job. The toughest part of my [rehabilitation]

was not knowing if I’d have a job to return to.”

On October 10, 2005, Swartz returned to work with no

restrictions and became the first amputee New York state trooper.

After his therapist and doctor said Swartz was ready to return to

work, he completed a two-page checklist, including such tasks as

quickly entering and exiting a patrol vehicle and rapidly pursuing

a suspect. The state police doctor then wrote that Swartz was

cleared to return to “full and strenuous duty.”

“Since I’ve been back to work, I can honestly say that I’ve done

everything from fighting bad guys, to chasing criminals through the

woods, to directing traffic in a snowstorm, and my leg is not an

issue,” he says. “I’m very proud to be back to work, but I don’t

want to just settle for that. There are six steps to amputee rehab;

the fifth is get back to normal and the sixth is to thrive. It’s

time for me to repay and help others who need it.”

Get the Right Mindset

His co-workers, who continued to visit him throughout his

recovery period, were thrilled to have him back. “It was sort of

like I was gone but not forgotten,'” he says. “They came to check

on me. Their support was worth its weight in gold and it made all

the difference for me.” Police and fire departments rallied around

him, holding fundraisers such as pancake breakfasts and bowling

tournaments to help offset his medical expenses. They even came

together to help complete construction on his log cabin home.

His amputee prosthetist was another motivating factor in his

rehabilitation. She knew just when to push him, telling him to

“quit whining” or when he needed to be told to slow down. Though

his insurance only covered 60 days of therapy and his prosthetic

leg at first caused sores on his residual limb, Swartz continued to

press his workout to the limit.

Swartz also was encouraged by a quote on the Otto Bock website

by President Bush, who said, “Americans would be surprised to learn

that a grievous injury such as the loss of a limb no longer means

forced discharge. In other words, the medical care is so good and

the recovery process is so technologically advanced that people are

no longer forced out of the military.” Swartz read that and

thought, “If those guys can return to the military, then I can

return to police work. It’s all about the mindset.”

Similarly, Dunville says, “Set your mind to what you want to

accomplish and don’t let that get out of sight.” Dunville, who

learned to walk on his prosthetic leg in less than a month, says

one of his first goals was to take his son trick-or-treating, with

his final goal to return to work. “Some feel they can’t return to

work after they become an amputee. Anyone who becomes an amputee,

not just firefighters and police officers, needs the proper mindset

to get back to [any job],” he says, adding, “Ninety-nine percent of

AFFA members have returned to their lifestyle; we’re still working

on the remaining one percent who desire to return to duty.”

All three–Scruggs, Dunville, and Swartz–feel the importance of

inspiring others. Scruggs created a website, www.karenscruggs.tripod.com, “to show other

amputees that life is what you make out of it after amputation,”

she says on the site. “Everything in life happens for a reason, and

I lost my leg for a reason. I believe the reason my life was spared

was to make a difference in the lives of other amputees. To help

other amputees cope with the loss of a limb and become

stronger.”

Dunville explains to schoolchildren that amputees are no

different from anyone else. Swartz speaks about survival and

courage. “I tell kids that we all have courage inside of us; we

just need to reach in and find it sometimes,” he says. “They run

home excited and tell their parents all about the trooper that told

them they had courage inside.”

They each strive to educate other amputees that their amputation

doesn’t have to mean the end of their career in protective

services, if they have the mindset and courage to fight the battles

ahead.

Sherry Metzger, MS, is a freelance writer with degrees in

anatomy and neurobiology. She is based in Westminster, Colorado,

and may be reached at [email protected]