The way we understand the movement of our own bodies plays an important role when learning physical skills, but a new study found the phenomenon works differently for people learning to use robotic prosthetic devices.

“When people first start walking with a prosthetic leg, they think their bodies are moving more awkwardly than they really are,” said Helen Huang, PhD, corresponding author of a paper on the work. “With practice, as their performance improves, people still do a poor job of assessing how their bodies move, but they are inaccurate in a very different way.

“This is the first study to look at this phenomenon in people using lower-limb robotic prosthetics, and it raises a number of questions that should help us improve people’s ability to walk with these devices,” said Huang, who is the Jackson Family Distinguished Professor of Biomedical Engineering in the Lampe Joint Department of Biomedical Engineering at North Carolina State University and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Everyone has a personal body image, an understanding of how his or her body is structured and how it moves, that informs the way it moves.

“We wanted to learn more about how and whether people who are using robotic prosthetics incorporate that prosthetic device into their body image,” Huang said. “Does that change as people become more familiar with using these devices? Is there any relationship between incorporating these devices into one’s body image and their performance using these devices?”

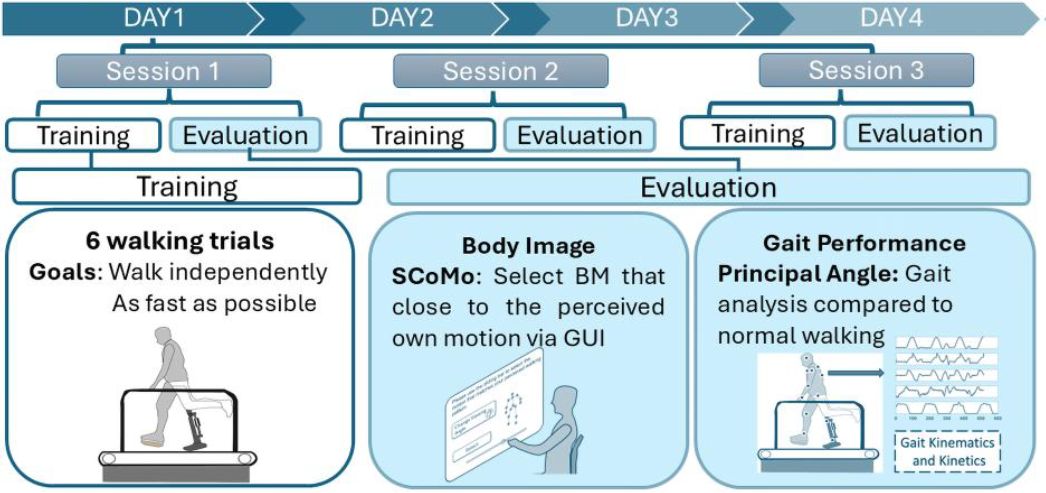

For the study, nine able-bodied study participants were tasked with walking using a robotic prosthetic attached to their knees bent at a right angle. Specifically, they were asked to walk on a treadmill as quickly as possible without touching handrails.

After each practice over four days, the participants were shown a computer animation that displayed a range of different biomechanical walking gaits and were asked to select which gait was closest to their recent performance using the prosthesis.

“Initially, participants felt their gait was more off-balance and stilted than it actually was,” Huang says. “By the end of the four-day study, participants felt their gait was more fluid and natural than it actually was. The performance of all participants did improve significantly over those four days. However, the participants were all still inaccurate at assessing the way their own bodies moved—just in a more confident way.”

The researchers found that one of the things study participants were focused on when assessing their own gait was the position of their torso. The participants did not place much emphasis on the behavior of the prosthetic device itself.

“One reason for this is likely because they are receiving very little direct feedback about the behavior of the device—they can’t see themselves moving,” Huang said. “This raises the possibility of improving performance by giving people visual or other feedback they can use to calibrate their body image and gait while training with the prosthetic device.

“It will also be important to address the overconfidence people have in their own movement skills,” Huang said. “If you already think you’re doing great, you’re less likely to put in the work necessary to get better—even if there is significant room for improvement. We think it would be valuable to find a way to give people a more accurate assessment of how their body is really moving.”

Editor’s note: This story was adapted from materials provided by North Carolina State University.

The open-access paper, “Projecting the new body: How body image evolves during learning to walk with a wearable robot,” was published in PNAS Nexus.