|

| Jonathan Bik races in the XTERRA America Tour. Photograph courtesy of CAF. |

Not all of us are destined for excellence. For example, even with a top-notch education, premium ingredients, and above-average intelligence, many people simply can’t bake an edible cake. It takes skill and talent. However, it is also true that many of us who have the skills and talent are not busy sweating over hot ovens and entering bake-offs. Why? It is not lack of ability that separates the skilled amateur from the elite competitor, but lack of inclination and drive. Whether you are a top-shelf baker, chess champion, or world-renowned athlete, the earmarks of an elite competitor are consistent: skill, talent, inclination, and drive. In the extraordinary efforts of challenged athletes, those traits are fueled by awe-inspiring levels of commitment and creative problem-solving. But perhaps even more important is the level of teamwork between the athlete, his or her prosthetist, and other members of the rehab team-an essential mix that not only makes elite competition possible but also helps to keep these extraordinary individuals performing at levels many able-bodied athletes will never achieve.

Case in Point

|

| Evan Strong, competitive skateboarder. |

Evan Strong, a 22-year-old transtibial amputee, has “the heart of a lion,” says his prosthetist, Mike Norell, CEO, Norell Prosthetics. “Usually, together with the patient, we plan what we’re going to do, but Evan has basically taken it upon himself to continue doing the things he did before.”

Strong was a competitive skateboarder before his accident in 2004. While riding his motorcycle down a two-lane highway, another driver crossed the center line and hit him. After losing his leg, he admits, “I wasn’t quite sure what I was capable of. I just knew that I wanted to recover, and my goal was to bring back at least 10 percent of what I had been capable of before.”

Once he was able to ride a skateboard again, the next step seemed natural. “I knew from that point I was capable of a lot more; then competition became an objective.”

It wasn’t easy. Strong was on crutches for a solid year after losing his leg. He was fitted for a prosthesis after about eight months, but there were problems. He had significant muscle damage in his quadriceps and below his knee, so it took around six months for his wounds to heal. Because of painful problems with circulation and resulting skin breakdown from wearing the prosthesis, reconstructive surgery was warranted.

“The surgeon wanted to perform an above-knee amputation, but I told him that we needed to try to keep my knee so I could skateboard again. He said, ‘Well, we can try, but your odds aren’t very good.'”

Strong was determined to keep and regain full use of his knee. More than six weeks after the surgery, he was able to try again with a second prosthesis.

|

| Pieper |

“Our largest challenge was his knee-flexion contracture,” said Robyn Pieper, PT, Physical Rehabilitation Center, Wailuku, Hawaii. “Without straightening of his knee, fitting him for a prosthesis would be very difficult. I recall times when Evan’s uncle or father helped to distract his leg [extend it] while I mobilized above and below his knee with as much force as I could.

“Evan tolerated all of this stretching and mobilizing most often with deep breathing. I don’t believe he even took pain medications,” Pieper says.

Once Strong’s knee was straight enough to receive a prosthesis, Pieper had him begin riding a stationary bicycle. “Within three weeks, he had progressed from level one to level ten-he maxed out the bike. Evan’s parents then bought him a road bike, and he began bicycling all over Maui, training for his first bicycle race. Soon after, he successfully competed and began his return to competitive sports.”

Now Strong competes-and wins-in adaptive skateboarding. His success motivated him to try things he had never attempted before his amputation. He also snowboards, rock climbs, and competes against able-bodied downhill mountain bikers-and wins.

“When your mobility is threatened and then you recover some of it, you are so appreciative,” he explains. “Now I do anything and everything that I can do.”

Strong wears a Norell prosthetic socket, an Ossur VariFlex® ankle, and an Ohio Willow Wood Alpha® liner, and has no additional, specialized components. “I walk, I race downhill mountain bikes, I skateboard, I rock climb, and I snowboard using the same prosthesis. I don’t know if anything else works better, but I’ve made this one work for me.

“I really believe being disabled is a state of mind,” he concludes. “Even if you aren’t capable of doing some things, you can be your own worst enemy and cripple yourself more than you actually are.”

|

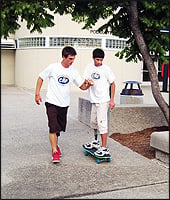

| Evan Strong and Troy Peckham. |

Norell agrees. “It’s all about attitude,” he says. “Even with 80- and 90-year-old patients with diabetes, you can’t predict who’s going to do well until they’re actually on their prosthesis and performing. Some people are just driven, and other people are not. Evan Strong is a very driven person. He’s a performer.”

Working with any active young person presents similar prosthetic challenges, says Norell. “You have to beef up their prostheses; the youngest kids break these things, and if you don’t go with acrylic lamination and carbon graphite everywhere, it’s pretty tricky.

“There are different ways to suspend, as well. You can’t just put them in a leg without supercondylar suspension. You have to lock in the knee as well because you don’t want any kind of pistoning. That would cause trauma because of their high activity level. You’ve got to consider an oversleeve, or try a bony lock, or possibly a suspension sleeve. You’re always going to shuttle lock them on the bottom, too, to prevent pistoning. I try to lock them in on the bottom and lock them in on the top.”

With a less active patient, such steps aren’t necessary, but “with someone like Evan, it’s all about function and nothing about cosmesis,” Norell chuckles. “He might be wearing an Alpha liner that’s three or four months older than it should be and needs to be replaced, but he’s going to tough it out-he’s going to duct tape his socket so he can keep going. That’s Evan.”

Case No. 2

|

| Jonathan Bik and Julie Gross, PT. |

Like Strong, Jonathan Bik had been active in sports before being seriously injured in an on-the-job accident at the Sacramento, California, Municipal Utility Department. Bik’s injuries resulted in a knee disarticulation amputation, and like Strong, the 31-year-old also began his recovery with no thought of becoming a competitive athlete. He had played soccer and other organized sports since age four, wrestled in junior high and high school, and was playing in an adult men’s soccer league at the time of his injury.

“After my accident, I had high hopes of what I could do, but it wasn’t for the purpose of competing-it was for the purpose of getting me whole so that I could get back to work and take care of my family,” he says.

Bryan Hayes, CPO, began seeing Bik immediately after his accident.

“Once he was up and walking, it was pretty obvious that he was going to be able to go beyond that, and he really wanted to push the envelope.”

Julie Gross, PT, prosthetic specialist at the University of California, Davis, remembers Bik as one of the most motivated patients she’s ever met. “I actually encountered him in the hall before he got fitted for his prosthesis,” she says. “When someone pointed me out and introduced me to him, he said, ‘I’m ready to go. What do I need to do?’

“And I said, ‘First you need to get your leg!'”

From the beginning, says Gross, “he was…determined that nothing was going to stop him. He was just a natural when it came to his gait. He came in wearing his prosthesis the day he got it and adjusted to it very quickly.”

After mastering golf with his “everyday” leg, Bik wanted to start running. “Julie was really excited that I wanted to do this,” Bik says. “She gets a lot of people who are bummed out about losing their leg and don’t like going to physical therapy. I loved it; I wanted to go. I knew if I went there and I hit this stuff hard, I could get myself back in business, stronger and quicker; that was my inspiration.”

Hayes rose to the challenge. “It was the first running leg we had ever made for an above-knee amputee, so we spent quite a bit of time changing our socket design and learning about knees and feet and what was appropriate for running,” Hayes says. “When we got the socket fit right, we had him run at the local track and worked on his alignment.

“Aligning an AK prosthesis for a runner is quite a bit different than it is for somebody who is going to walk, and there’s no handbook for fitting athletes,” Hayes continues. “You’ve got to be very creative. All the forces in the socket are magnified when [a patient] runs, so you have to be out there with them and see their leg right after they’re done running. How it is in the office versus how it is after a couple of miles of running is completely different.

“A lot of it was trial and error,” Hayes says. “We’re still experimenting. Now that he’s expanded into triathlons, we’ve been searching for ways to improve his cycling legs.”

Hayes points out some of the unusual aspects of Bik’s case: “Jonathan is a little different in that he’s a knee disarticulation patient, and he can tolerate end bearing. So we passed over an ischial containment socket in favor of a short socket because it allowed him a little better range of motion at the hip, and he was more comfortable with that design as an everyday leg. For the first year he was running, the challenge was getting him used to total end bearing.”

As Bik’s activity has improved, Hayes says, “He’s actually in better shape, according to his father, than he was when he was in high school. His endurance has improved with his physical fitness, and the changing volume of his leg has presented us with a lot of socket fit issues. And as he has gotten more competitive, competing in national and pro-level events. It comes down to how many seconds or minutes we can shave off in his events.”

|

| Bik assists at a Challenged Athletes Foundation clinic. |

The rehabilitation was truly a dedicated team effort, Bik says. His rapid progress at every level precipitated interaction between patient, therapist, and prosthetist. “He was going so fast, it was hard to keep up with him, so we all talked together more frequently,” Gross says. “Because he is so highly skilled, we got to try new things and learn from Jon-Jon taught me a lot about running.”

“We learned together, and it worked out really well,” Bik says. “Once we reached a certain level, I started going to mobility clinics offered by the Challenged Athletes Foundation (CAF), and comparing notes with other athletes. I really don’t think I could have done it without any one of those three.”

Bik stresses the importance of the opportunities for networking and peer support provided through CAF. “I got to see and hear what other people went through and how they got help. They’re on the news, they’re in magazines, they’re doing things that I really wasn’t thinking about doing while lying in the hospital. It truly inspired me.”

Now Bik offers his own services and experience to CAF, assisting and teaching at running clinics to help other athletes get started.

Bik still works for the Sacramento Municipal Utility Department, and he and his wife are expecting their third child. Thanks largely to CAF, he says, he has completed two XTERRA triathlons and qualified for nationals in October.

So what’s the formula for achieving excellence? From where Bik and Strong stand-at the top of their games and striving still to be better, faster, stronger-it looks very much like Attitude + Relentless Effort + Skilled Support = Personal Satisfaction.

Judith Philipps Otto is a freelance writer who has assisted with marketing and public relations for various clients in the O&P profession. She has been a newspaper writer and editor and has won national and international awards as a broadcast writer-producer

.

Active … or Elite: Athletes Seek Their Own LevelPeter Harsch, CP |