It takes a keen eye to see that Laurie Richmond wears a prosthetic left hand. “Either people notice it immediately, [especially] if I have the hook on, or they don’t notice it at all because I’m so efficient with it…. When…they do notice it, they are…completely taken by surprise because it wasn’t a focus point for them at all,” she says.

Despite her comfort and agility with using a body-powered prosthesis, Richmond says she wears a hook much less frequently these days. About eight years ago, Richmond, 49, a lifelong prosthesis wearer was fitted with a myoelectric hand. As the occasion or activity warrants, she switches between a Motion Control (MC) Hand or Electronic Terminal Device (ETD), both of which are equipped with an optional flexion wrist or a body-powered hook. “I’ve loved…having the option of not having the harness and also the attractiveness of [the MC],” she says.

“I work in an office, so I wear [the MC] during the day, [and] I wear it when I go out,” she says. “But typically for all the things that I want to do—I’m a gardener, I’m a biker, I’m a runner, I’m a hiker—I have my ETD on or my body-powered hook. I wear a Regal glove [by Regal Prosthesis, Hong Kong, available through Hosmer Dorrance, Campbell, California, in the United States] on my myoelectric hand, and it’s beautiful but also sensitive to cuts and abrasions. Using the ETD and hook during many outdoor activities helps me to keep the glove looking nice.”

Growing up, Richmond didn’t have a choice about whether or not to wear her prosthetic hook—her parents were insistent that she wear it. However, she had choices about what she could do or try to do while wearing it, and she chose to do or try anything she wanted.

Why Not Me?

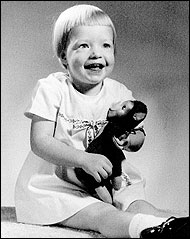

Richmond says she was fit with her first harness and socket by the time she was 13 months old and a prosthetic hook by the time she was two. Richmond attributes her adeptness at using her prosthesis and her ability to adapt to her “new normal” to the prosthetic care she received at Shriners Hospitals for Children-Portland, and her mother’s persistence.

It’s a controversial subject: As a parent of a child with a congenital amputation, do you or don’t you insist that your child wear a prosthesis? Richmond’s parents decided that it was important. “I have an incredible life,” she says. “I’m grateful to my parents for all the ways in which they helped me adapt. They did not put limitations on what I should or shouldn’t do physically, nor would they allow others to limit me.” Richmond says this empowered her to develop her own sense of ability.

“It was as if I had two [real] arms, and they were used very well,” Richmond recalls. Just like any other kid growing up in the country, she learned to swim, ride a bike, and ride and show horses. “When I was riding my horse, I could grab branches…, blackberries, [and] thistles…. The people I was riding with were so jealous because I could go by all of those things uninjured, and they had to suffer [cuts and scratches], she says, adding, “I used [my prosthesis] as a hammer; I used it as a pair of pliers…. I took advantage of the benefits of having it. I always said…,’I don’t think having a hook is such a bad thing. Look at all the things I can do that you all have to find a tool to do….'”

Richmond’s parents raised her to believe that being born with a limb deficiency did not make her unique, just different—different in the same sense that some kids have brown eyes and others blue, some are tall and others are short, and some have ears that stick out and others don’t.

When Richmond told her mother that kids were picking on her, she recalls her mother saying, “You know, you’re not the only one—lots of kids get picked on for lots of different reasons.'”

Richmond says she envied the little girls who could swing on the monkey bars, recalling that she thought it seemed “like a ten-finger operation.” Even still, she practiced with fierce determination on her home jungle gym—that is until her residual limb lost suction and came out of the socket. Unable to release the harness, she hung from the jungle gym bars, and her father had to rescue her.

Her teenage and young-adult years presented different issues. Wearing a body-powered device was cumbersome at times, and she did not feel comfortable wearing strapless or sleeveless tops. Richmond says she hated being without her arm. She recalls when she was in junior high school and “being in the stupid community showers and I’d have to take my arm off. That was very uncomfortable for me.” Then there were times she tried to cover up her prosthesis, such as in her Jazzercise class during her early 20s. “I wore a long-sleeve T-shirt [over my leotard]…,” she says. “The people [at the gym] were so encouraging and…[in] under six months I was wearing a sleeveless leotard like everybody else’s…. That’s such a funny time for a young woman anyway. You’re coming out of your teens, [and] now you’re this adult…trying to figure out all this stuff.” Although not so much feeling sorry for herself, Richmond admits going through the “why me’s?” during this time. “And I finally said to myself, ‘You know what? Why not me?'”

Coming to a deeper level of self-acceptance is something Richmond says she continues to benefit from. Yet self-acceptance doesn’t mean that a woman still can’t be concerned with how she looks.

Prosthetic Aesthetics

Support authors and subscribe to content

This is premium stuff. Subscribe to read the entire article.