In “Design and Outcome Considerations for Hip Disarticulation Patients, Part I” (The O&P EDGE, November 2021), I gave a general overview of this patient population. I will now share casting techniques that I have used and found helpful for people with hip disarticulation amputations and explore modifications for the molds after casting.

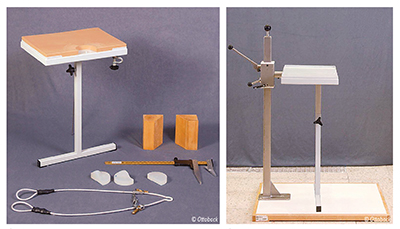

Figure 1 displays an Ottobock casting apparatus. This setup includes the casting plate, hip tension belt, form block that will accommodate the ischial tuberosity caliper with angle scale, and casting blocks.

It should be noted that the method described in this article is only one way to get an impression for a patient with a unilateral hip disarticulation. Other common casting methods are total suspension casting, use of the Martin Bionics Bikini Socket Hammock Casting Stand, and the anatomical compression contour method developed by Bobby Latham, CP, and Alex Hedquist, CPO.

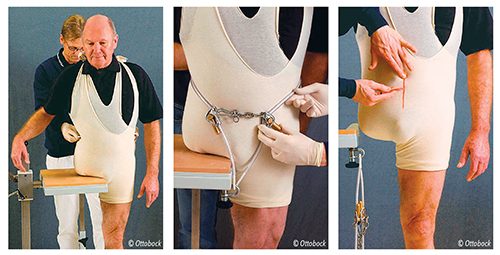

Figure 2. The hip apparatus mounted to the hip casting apparatus.

Any casting technique should be seen as a fitting system, meaning that the patient will be able to best make use of the hip joint only if they have an intimate fit of their socket. Make sure all necessary measurements are taken, such as mediolateral (ML) and anterior/posterior (AP) of the hip and waist, circumferences, and lengths/heights of the mold. You can use the body caliper gauge to determine the ramus angle. This is important for helping with the line of progression and socket alignment to hip:joint ratio. If using a snug-fitting stockinette, make sure to mark all bony landmarks and the midline of the body and pelvis on the involved side.

Figure 4. Adjust the tension belt.

Figure 5. Mark the center of the body.

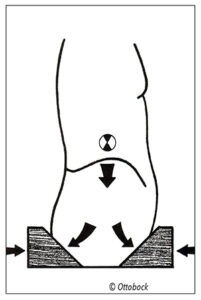

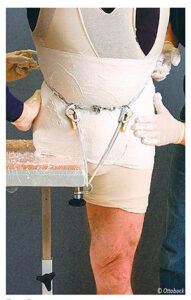

Once the casting stand has been assembled, make sure the tension cable is taught. This will help outline the iliac crest grooves to aid in suspension. Next, apply the appropriate length plaster bandage strip from AP to establish a good base contour. I usually use a 10-inch bandage overlapped four to six times, with the length determined by the patient’s size. Then I use a 10-inch plaster bandage from ML and wrap it in a circumference, locking in the original AP strip. Wrap the bandage anterior, move to inferior, then laterally around the sound side hip above the iliac crest. It is important that the plaster mold extend to midline anteriorly and posteriorly. Last, have the patient slide back onto the casting apparatus, then reposition the anterior and posterior blocks, flattening the plaster. If using the Martin Bionics Hammock Casting stand, this same principle is used with the AP plates to compress the soft tissue. The hip joint placement can be identified after the plaster hardens. If you have done a good job with the cast, very few modifications will be needed.

Modifications are a continuation of the fitting process. The goal is that if enough compression was applied to the AP directed force where needed, there should be less time spent modifying a plaster mold.

All landmarks are used as a map or reference for where the mold is in space. A quick comparison of your measurements to the measurements on the mold is the starting point. The comparison should be within approximately 1cm of difference to ensure the patient has good control of the prosthesis. The waist groove on the mold is expected to be overdefined. This can cause discomfort in the socket if left unmodified. Be careful to only do reduction over soft tissue to prevent skin breakdown over bony areas/landmarks; adding plaster will most likely be over bony landmarks such as the anterior superior iliac spine and iliac crest.

Figure 9. A Martin Bionics Bikini Socket Hammock Casting Stand.

With any design, the patient presentation must be the first consideration. What works for one person may not work for the next. This is also true for clinicians learning how to cast and modify molds for people with hip disarticulations. By having several methods for casting and modification to choose from, the best outcome for the patient and practitioner can be achieved.

Part three of this series will examine alignment, biomechanics, and component selection.

Ahmahn Peeples, CPO/L, ACSM-CPT, EIM, is a clinician with more than 15 years of experience in patient care and education. He is a staff clinician and outcomes southwest regional champion with Hanger Clinic. He can be contacted at [email protected].

References

- Endean, E. D., T. H. Schwarcz, D. E. Barker, N. A. Munfakh, R. Wilson-Neely, and G. L. Hyde. 1991. Hip disarticulation: Factors affecting outcomes. Journal of Vascular Surgery 14(3):398-404

- Boyd, H. B. 1947. Anatomic disarticulation of the hip. Surgery Gynecology Obstetrics 84(3):346-9.

- Hampton, F. 1966. Northwestern University suspension casting technique for hemipelvectomy and hip disarticulation. Artificial Limbs 10(1):56-61.

- Littig, D. and J. Lundt, J. 1988. The UCLA anatomical hip disarticulation prosthesis. Clinical Prosthetics and Orthotics 12(3) :114-8.

- Shurr, D. G., T. M. Cook, J. A. Buckwalter, and R.R. Cooper. 1983. Hip disarticulation: A prosthetic follow-up. Orthotics and Prosthetics 37(3):50-7.

- St. Louis-Sanchez, M. 2014. Improving fit + function for the hip disarticulation patient. The O&P EDGE 13(8):24-32.