In a few brief, horrifying moments, more than 300,000 lives were snuffed out, and tens of thousands of others were changed forever. The magnitude 7.0 temblor that shook Haiti to its core on January 12, 2010, was the strongest to hit the island nation in 200 years, according to a report on msnbc.com. Even an impoverished country accustomed to hardship was staggered by the enormity of the tragedy. It was a disaster in the truest sense of the word.

An overwhelming need for prosthetic aid was immediately perceived, and organizations and individuals from the global community responded. Looking back, we consider the quality and effectiveness of that response—examine what was accomplished, assess its impact, and consider those needs that remain to be addressed.

Getting a Handle on the Numbers

Patients await care at the Healing Hands for Haiti P&O clinic. Photograph courtesy of Daniel Cima/American Red Cross.

Getting an accurate initial assessment and effectively planning a rapid response were major challenges for the earliest responders. Al Ingersoll, CP, P&O program director for Healing Hands for Haiti (HHH) had volunteered in Haiti for many years before moving with his wife to Port-au-Prince in April 2010. Shortly after the January 12 earthquake, HHH partnered with Handicap International (HI) to relocate the badly damaged HHH P&O clinic. With the help of HHH technicians, equipment, and materials, the HHH clinic became the first facility in Port-au-Prince to regain operational status.

As part of the January 2010 HI-sponsored injury assessment team, Ingersoll originally estimated that 1,500 amputations had been performed immediately after the earthquake. “The estimate was revised to 2,000-4,000 because at the time we could not get reports from a few other countries who had significant responses….

“Most hospitals did not keep records for the first week or two after the earthquake and had no idea how many amputations had actually been performed,” he continues. “As the only full-time provider of prosthetics and orthotics in Haiti, HHH ‘only’ provided 50-100 devices per year, and according to the World Health Organization (WHO), a country of Haiti’s size might have 8,000 people with an amputation. Many post-quake providers of prosthetics report more than half of the beneficiaries are people with pre-quake amputations. We hope follow-up studies will better document actual numbers.” (Author’s note: Based on their observations in field hospitals over a five-month period, the U.S. Public Health Service Centers for Disease Control (CDC) determined that a study on the subject was necessary, but it had not yet been initiated, and the cholera outbreak put everything on hold, according to Sridhar V. Basavaraju, MD, CDC’s Lt. Commander.)

Patients and their families often travel many miles to receive prosthetic care. Photograph courtesy of Hanger Prosthetics & Orthotics.

“I am still of the opinion the actual number of earthquake-caused people with amputations is lower than many have reported; my current estimate is 1,200-1,500 people have survived with an earthquake-caused amputation. By January 12, 2011, I estimate 2,000 prosthetic limbs will have been fit, thousands of custom and prefabricated orthotic devices provided, basic P&O education efforts started, and, most importantly, many people and families assisted,” Ingersoll concludes.

Robert S. “Bob” Gailey Jr., PhD, PT, spearheaded the University of Miami, Coral Gables, Florida, Project Medishare prosthetic effort. He notes that their newly established Hospital Bernard Mevs is the largest trauma and rehab center in Port-au-Prince. He agrees that the number of earthquake-caused amputations ranges from 600 to about 2,000. “The problem is we can’t get a handle on it because 1.6 million people are displaced in the tent cities,” he says. “People will simply not know to get prosthetic care so we don’t see them, while other people go from one facility to the next saying they need a leg, until they find a leg they like. The official numbers are often inflated, but the assessment that was done by the military was closer to 600; the one that was jointly filed by the non-governmental organizations (NGOs) is between 1,500 and 2,000.”

Kevin Carroll, MS, CP, FAAOP, notes that the earliest projection based on his initial visit—that as many as 10,000 amputations might occur in the earthquake’s wake—was thankfully overcautious. “There are more like 1,500 amputees as a result of the earthquake, which is good news,” he says.

Ivan Sabel directed efforts of the Haitian Amputee Coalition, a partnership between of the Hanger Ivan R. Sabel Foundation, the Harold & Kayrita Anderson Family Foundation, Physicians for Peace, the Catholic Medical Mission Board, and Donald Peck Leslie, MD, of the Shepherd Center, Atlanta, Georgia, to establish a prosthetic and rehabilitation center at the undamaged Hôpital Albert Schweitzer (HAS), 60 miles north of Port- au-Prince in Deschapelles, Haiti. The clinic has been functional since February 22, 2010. By December, it had fit close to 700 amputee patients, two-thirds of whose limb loss resulted directly from the earthquake.

Too Many Helpers?

According to Ingersoll, “P&O service in Haiti currently is provided by 15 organizations in various capacities—most full time and a few only open during visits of short-term volunteers.”

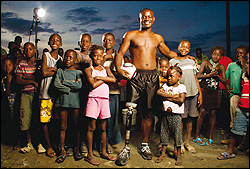

After being fitted with a prosthetic leg, Wilford Messine (center) began playing soccer. Project Medishare has hired him to help fellow Haitians overcome the physical and cultural challenges of being an amputee. Photograph by Omar Vega, courtesy of Project Medishare.

Since there is no oversight, per se, does that create a situation where the left hand doesn’t know what the right hand is doing?

“A lot of the people that just popped in to provide emergency prosthetics during the initial crisis are no longer there,” Gailey says, “so things are stabilizing somewhat. Since there’s no formal organization within Haiti, the NGOs have taken it upon themselves to hold a monthly meeting where everybody gets together to discuss their relative situations. They collaborate on an as-needed basis, and that’s the extent of it.”

Ingersoll further explains: “Coordination by a government agency is loosely defined by a registration process and acknowledgement of activities and not a formal oversight ministry. The NGOs are in frequent contact with Haitian government ministries and now meet once per month to update on activities and be informed of new developments. Depending on funding, location, focus of operation, and future plans, the groups are working both cooperatively and independently. The oversight needed is hard to define because…basic needs are being met, education efforts are under way, and some collaboration with government is necessary.”

In that case, could just anybody put up a tent and hang a prosthetist’s shingle?

“There are currently no restrictions on establishing a prosthetic effort in Haiti,” Sabel says, “although there has been governmental concern expressed over the influx of…non-governmental organizations that have been proliferating…. I think the problem for the future is a need for much greater cooperation and coordination among the interested parties.”

The existing level of cooperation is far from deplorable, however. Medishare’s Director of Prosthetics, Adam Finnieston, CPO, LPO, says he is pleased by the consolidation he sees among the prosthetic providers serving in Haiti. “I’ve been very proud of our industry as a whole, and the people who put aside their home-court competitiveness in order to work together to help the Haitians.”

Triumphing over Logistical Challenges

Each of the teams has more than its share of hair-raising tales to tell of the Wild West atmosphere, the privations, and the obstacles they faced during those early “pioneer” days:

Hanger Ivan R. Sabel Clinic

Medishare Hospital in Haiti. From left, Wilford Messine and Davor Krcelic. Krcelic is chief prosthetist and orthotist at the Medishare Hospital. Messine is a Medishare technician and was also one of Krcelic’s patients. Photograph by Omar Vega, courtesy of Project Medishare.

Carroll tells of burned bodies still lying in the streets when he arrived in the country. “It was a pretty devastating situation,” he says. “There were a lot of severe injuries, a lot of suffering women and children. Our goal initially was to determine what we could do to help people who lost limbs, so we went from tent to tent, school to school, and building to building. We quickly found that they were being stabilized, but we could immediately see that without early intervention, there could be problems. Resulting from instantaneous crush-type injuries, the limb shapes were not your typical U.S. amputation; the surgeon was really just trying to close up the wounds and move them forward. We feared at the time that many of these amputations were going to have to be revised, but fortunately that has not been the case.”

The HAS prosthetic center’s recipe for success relies on the seven native Haitian staff working with the Haitian Amputee Coalition volunteers, Carroll says. “Four members of our clinic’s staff are technicians whom we taught on site, and all have done a remarkable job. Most practitioners in the United States wouldn’t get to see 700 amputee patients in a lifetime, yet our clinic has served that many in just nine months. These dedicated workers have learned a huge amount in a very short period of time, and they’re still learning.”

Sabel points out, “It’s not realistic that we stay there forever, and since there is talent in Haiti, and there is close to 70 percent unemployment, it’s a perfect opportunity for us to give employment to some Haitian folks and to train them and make them, with our support, able to sustain the effort.

“We wouldn’t have gone into Haiti had it not been consistent with our Foundation’s mission of sustainability. What makes this particular mission very realistic for sustainability is the fact that it’s in our hemisphere. We’ve gone to Turkey after the earthquake, we’ve been in Afghanistan, we’ve done a lot of what I call missionary-type work, but it’s very difficult to sustain an outpost in the long term when they’re a world away. I get to Haiti in two-and-a-half hours; from a logistical standpoint, that makes it realistic.”

Practice manager Jay Tew, CP, the first lead practitioner at the Hanger clinic in Haiti, recalls early struggles to convert a warehouse into a fully functional O&P lab. “Logistics were always an issue and will continue to be an issue for us there, but it seems to be getting better,” he says. “When I arrived, 13,000 pounds of material had already been shipped in, including cargo containers full of equipment, so we had all the essentials we needed to fabricate limbs on the ground—of course we didn’t have electricity! We were working every day on pure faith and adrenaline. Within a couple of days, we got electricity and water. Water was only available a couple of times a day, so we’d fill 55-gallon trash cans so we could pull out of that all day to use for casting and plaster.”

Creature comforts were also an unknown. “I didn’t know where I was going to be living, sleeping or working—I had only seen pictures of the place. It was a true leap of faith, fueled by my confidence in the support network with me and behind me. Once I arrived, I found my housing was better than I could have imagined.”

At the time of this writing, Tew was preparing to return to Haiti for a second rotation at the Hanger Clinic in January. This time, he says, the experience will be different. “Now I know the people in the community, I know the patients and the medical teams. There’s an infrastructure in place that will allow me to start working immediately, with no learning curve, no fear factor or uncertainty or anxiety.”

Project Medishare

About two weeks after the quake, Finnieston traveled to Haiti on behalf of Project Medishare. His goal was to evaluate the situation and, with the help of Bob Gailey, put together a prosthetic program. Finnieston recounts the adventure, including being trapped in the country and forced to fly home on a military transport plane. “Those were the Wild West days,” Finnieston says. “There was no law; it was crazy.

Twenty-year-old Evana Prince (sitting above) had just returned home from school when the earthquake hit. “I was taking a nap when everything started to shake,” she explains. “I ran out of the house and a building fell on me.” She was rushed to the hospital, but the injuries to her leg were too severe, and doctors amputated the limb. “I never thought I would walk again, but now that I have this leg I can do things that I couldn’t do when I had to walk with crutches.” Photograph courtesy of Daniel Cima/American Red Cross.

“I went down for three or four days and evaluated what was there, what was on the ground, how many people I saw, how many amputations at the Medishare [tent] hospital. It was mayhem, but it was certainly a testament to that group that they were able to put that together and the lifesaving surgeries in the quantities that they did down there. I started wrapping limbs, and I started pre-prosthetic care on all the patients that I saw, while looking to see what type of processes and procedures would be applicable to that environment.”

During his brief information-gathering visit, however, Haiti’s wide-open borders shut down with a crash. “Customs, NSA [National Security Agency], everybody was on the ground reacting to the unauthorized transport of large numbers of Haitian orphans,” Finnieston recalls. “Everything shut down; you couldn’t get on a plane unless you were manifested properly. To get home, I had to hitch a ride on a C-17 U.S. Air Force military transport plane that would transport me to U.S. soil—but they wouldn’t tell me where until we arrived!”

The Medishare hospital has since moved to a brick-and-mortar structure and is called Hospital Bernard Mevs, which has a full-time prosthetist, a full-time therapist, and full-time local technicians on staff, supported by volunteers who rotate in for one-week tours. More technicians continue to be trained, and Finnieston says the program is expanding significantly. “We just sent down a container full of supplies, and we have a new building going up just for the prosthetic facility at the Hospital Bernard Mevs, so we are in expansion mode at this moment.”

As director of prosthetics, Finnieston supports the clinic from Miami, modifying all the models that are fabricated in the United States, enabling and encouraging more manufacturing at Hospital Bernard Mevs. He also supervises the shipment of “every rivet, piece of plastic, and plaster bag that goes down there,” he explains. “Thus I will be going back and forth as needed for at least the next two years. I have a feeling this is going to be a lifelong venture for me,” he muses.

Delivery Delays

In support of the Haitian Amputee Coalition, Ron May, president and COO of SPS, Alpharetta, Georgia, helped facilitate the provision of essential components and supplies that had to be transported to Haiti. May describes the difficulties and delays involved in shipping equipment and supplies into a port where irregularities are otherwise referred to as “business as usual.”

Randy Roberson, CP, CPed, works with a patient at the Hanger Clinic in Haiti. Photograph courtesy of Hanger Prosthetics & Orthotics.

“In the beginning, it was not only supplies but equipment that was necessary, and that’s not something you put in a UPS box and hope it gets through,” May says.

“Through a private donor’s personal plane and other shipments, we were able to transport more than 13,000 pounds of fabrication machinery, equipment, donations, and significantly discounted items from a number of suppliers from an Atlanta airfield into Port-au-Prince. You could literally take it off a plane, put it on a truck, and take it up to the Hôpital Albert Schweitzer,” May recalls. Later, delivery depended primarily on shipping via UPS containers.

About five or six weeks post-quake, however, the government began to get back on its feet, and the typical incoming shipment roadblocks began to reappear. “Some of the container shipments we sent down were three-and-a-half months in transit,” May discovered, “and we had to use all the resources and contacts at our disposal to get the containers and, sometimes, the UPS shipments released. In most cases, it took at least three months to get anything through, other than those initial emergency shipments.”

A January 26, 2010, Reuters news report noted, “Despite the best intentions of the international community, Haitians have little faith they will see the billions of dollars in aid pledged to rebuild their earthquake-shattered country, which international monitors rate as one of the world’s most corrupt. From successful businessmen to refugees scraping to survive in squalid tent camps, Haitians said they expect that a good portion of any money sent will flow straight into the pockets of corrupt government officials.”

Terms like fraud, corruption, political impropriety, government instability, and decrepit infrastructure, are commonly used by the mainstream media in describing Haiti’s approach to doing business; these words would appear to apply to officials in charge of shipping as well. As of December 2010, three-to-four-month delivery delays were still the rule of the day, May confirms.

The Technology Question

One of the biggest challenges facing clinicians in the first weeks following the quake was determining—and agreeing upon—the most appropriate prosthetic technology to use for Haiti’s amputees. Carroll says that the Haitian Amputee Coalition engaged in lengthy debates on the subject before committing to choices they felt the volunteers would be most comfortable with and need little or no retraining to fit; e.g., modular European components. A waterproof plastic Seattle foot with an all-plastic cover has worked well in Haiti, he reports, often used in conjunction with a Medi knee. Quadrilateral sockets are used for transfemoral patients, and simple transtibial sockets are used for below-knee amputees.

“We have brim socket shapes for the AKs already on the ground there, so we can teach and make it easy to do,” Carroll says. “It’s important that our choices are durable, lightweight, standard endoskeletal selections that prosthetists from Europe, the U.S., and of course the Haitian people that we train, will be able to manage easily,” he adds.

Upper-limb prostheses have been a different story, according to Ingersoll. “Upper-extremity prosthetics have been provided in very limited quantities,” he says. “Haitians are very aesthetically conscious and frequently will not use a split-hook equipped prosthesis; they will only accept a more expensive cosmetic glove-covered passive hand, which requires frequent glove replacement.”

He also notes that overall, prosthetic component technology and fitting techniques varied from prefab sockets to custom fit sockets; hard sockets to custom gel liners; and in-country CAD/CAM designed and produced, casted in Haiti and made in other countries.

“In the past,” Gailey says, “It was understood that in a developing nation like Haiti, we had to use low-cost, basic prosthetic components. But we’re finding that the people that we’re training are capable of using more sophisticated prosthetic techniques and fabrication, and also that they are willing and capable of taking advantage of the more sophisticated componentry, so we’re all trying different things. At our hospital, we’re using everything from the modular prosthetic system from Össur—which is the direct fit system—all the way up to Biosculptor CAD system and everything [in] between. All have had success.”

Interruptions to the Continuum of Prosthetic Care

Not surprisingly, the recent cholera outbreak in Haiti has directly affected P&O services by diverting personnel to the response, Ingersoll points out. “Election-results violence is the newest concern.”

Gailey agrees. “Medical facilities are now being overrun by people who have to be hydrated as rapidly as possible, so there’s very little concern about those who need a prosthesis at this time. In our hospital, it’s about saving lives. We’re still fitting people with prosthetics, but because of the cholera patients, people don’t want to get close to the hospitals. Primarily the cholera outbreak has caused unrest because the people are scared; they don’t understand that it is a bacteria that comes from not washing hands and not drinking clean water; unfortunately, clean water can be hard to come by at times.”

Ian Rawson, MD, HAS’ director, noted in December that the number of patients with cholera that they had treated has outpaced the number of patients they treated after the earthquake—more than 1,000 in just a few weeks—and more continue to come in for treatment. “The earthquake [caused] the largest number of patients we had ever had at any given time; now the cholera has surpassed it. The earthquake victims all came at the same time, but the cholera patients have been arriving over the past two months. It is a terrible burden on the hospital as well as the patients because we didn’t plan on it, didn’t budget for it, but we have to take it all in stride.”

Is there an end in sight?

“No,” Rawson says. “Cholera will always be in Haiti, whether at an epidemic level as it is now, or just endemic. Typical of epidemics, there’s an initial phase in which many people sicken and a high proportion die; then it slows down and picks up again, repeatedly. Basically, populations and the disease accommodate to each other, so it’s always there.

“Just over a year ago, in 2009,” he reflects, “we had no idea we’d be taking care of 1,000 earthquake victims, almost 1,000 amputees, and 1,000 cholera victims—no idea at all. We had to move quickly during this year to redesign ourselves. We are most appreciative of the generosity and professionalism of the Hanger group.”

Political Roadblocks

Healing Hands for Haiti (HHH) Prosthetic and Orthotics Clinic 2010. HHH receives financial support from the Red Cross Network. Photograph courtesy of Daniel Cima/American Red Cross.

Sadly, much of the $9.9 billion donated or pledged to aid Haiti (per The New York Times, November 29, 2010), is still in the hands of those who raised the funds due to their concerns about governmental instability and disarray, and a desire to wait for a new regime to take charge following the November 2010 election. (Editor’s note: According to the Haitian Internet Politics & Government Resource Center website BèlPolitik.com, the second round of the presidential elections has been postponed and, so far, no new date has been set.)

“Hopefully, over time,” Sabel says, “it will be possible to deploy all the charitable money that has been raised and deploy it appropriately, with a government that will be able to rebuild the infrastructure of Haiti.” Sabel notes, however, that funds donated to the Hanger Ivan R. Sabel Foundation’s efforts in Haiti have already gone to Haiti, with no administrative overhead costs.

Finnieston concurs. “It’s a bad situation. The first thing that country needs is a government—a real, cohesive, non-corrupt government, but I don’t think that will ever happen. I’ve been stopped at gunpoint trying to get our prosthetics out of a warehouse. Until the political infrastructure and questionable practices in Haiti are addressed, [that type of treatment will] be business as usual.”

Gailey adds, “In order to provide care and import your supplies, your organization must be registered and approved by the Ministry of Health, as are Medishare, HHH, and other NGOs. Although theoretically we won’t have to seek re-approval after the election, who knows? Everything changes in Haiti.”

Tomorrow’s Roadmap

A Project Medishare patient walks with her new prosthesis while her brother holds her crutches.

Photograph by Omar Vega, courtesy of Project Medishare.

“Our goal for the future is very simple,” Sabel says. “One of the missions of the Haitian Amputee Coalition is to create a sustainable program in Haiti—not just go in, fit a bunch of people, and leave. To that end, in addition to our own Coalition volunteers, we have employed four Haitian technicians whom we have trained and who are becoming much more self-sufficient as time goes on. In 2011, we will begin to transition most of the day-to-day operations over to our Haitian counterparts.

“We are also looking at establishing a presence in Port-au-Prince. It has not yet been determined whether we’ll do that in coordination with one of the other organizations, but discussions are currently in progress with several different organizations.”

HHH is looking forward to relocating their Port-au-Prince presence to new quarters in 2011, Ingersoll announces. “The International Committee of the Red Cross Special Fund for the Disabled [ICRC-SFD] has assisted HHH since 2005 with training, materials, components, and equipment. They have recommended and obtained American and Norwegian Red Cross funding for a new building to reestablish their P&O and therapy clinic in the center of Port-au-Prince. The formal memorandum of understanding was signed on November 15, groundbreaking was slated to occur soon after January 1, and the center should be operational by the end of 2011.”

Not just new locations, but new methods of helping are the focus of Carroll’s future plans for Haiti. “We have patients all across the U.S. who outgrow their prostheses over time, or their function level changes, and they have useable components that they want to do something with. There’s a great amount of pre-owned componentry from the U.S. that could be donated to Haiti—and would be very welcome there.” Plans for developing this program are still in progress.

In addition to the new prosthetics facility that has been built, Medishare is also moving forward with a new program—Hope for Haiti’s Children—funded by the Knights of Columbus, which has provided a $1.2 million grant to provide prosthetic care for every child in Haiti, Gailey reports. “Not for one year, but for two and possibly three years, enabling us to change out the limbs and put together a return-to-school and a return-to-sport program,” he says.

“In Haiti,” he continues, “the population is 80-percent Christian and 100-percent voodoo; prior to the earthquake, they believed that an amputee had been punished with limb loss as the consequence of some horrible sin and should be shunned and avoided. That stigma stays with them throughout their life. Through this new Knights of Columbus program, we plan to change the attitudes of the children and their peers—to educate future generations that there’s nothing wrong with your classmate with limb loss; he or she is just like you.

“This program is one of the coolest outcomes of Haiti’s crisis: a wonderful new way to offer hope for Haiti’s children.”

Judith Philipps Otto is a freelance writer who has assisted with marketing and public relations for various clients in the O&P profession. She has been a newspaper writer and editor and has won national and international awards as a broadcast writer-producer.

Fears and Frustrations

Though much has been accomplished in the year since the earthquake in Haiti, the experts interviewed for this article stress that many challenges remain. A few of them reflect on those challenges and note a number of victories that should be celebrated:

Support authors and subscribe to content

This is premium stuff. Subscribe to read the entire article.