Medial tibial stress syndrome (MTSS) is a common injury of the lower leg that affects runners, athletes, dancers, and other active patient groups. It is an exercise-induced overuse injury resulting from weight bearing activity. The previously used term, shin splints, is a poor, vague descriptor that has essentially been retired from the medical literature. It is important to use the correct terminology describing this syndrome as there are several conditions of the lower leg that present similar symptoms but have distinct diagnoses.

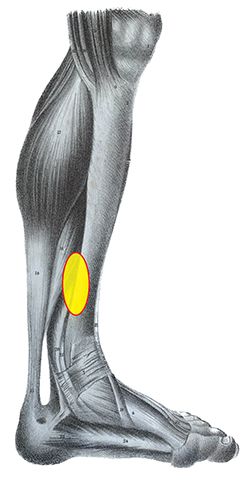

MTSS is often described as intense pain in the lower part of the tibia occurring along the posteromedial border, over a length of at least 5cm (Figure 1). It is a musculoskeletal injury that affects up to one in five runners and is also prevalent in military recruits. In its early stage, the pain is induced by exercise but may dissipate as the session continues, and it usually resolves with rest. Examination of the leg indicates diffuse pain in the tibia along the medial border, in a region about two-thirds distal. Some researchers view MTSS as part of a continuum that begins with tissue injury, but if untreated it may lead to reduced bone density and stress failure. Accordingly, in its later stages the pain may last beyond the period of activity.

Support authors and subscribe to content

This is premium stuff. Subscribe to read the entire article.