While I have learned many lessons over the course of my residency, the one that stands out the most in shaping my outlook on patient care came from outside O&P. Dan John, a strength and track and field coach, said, “The older population is a window to us all.” As a society, we are living longer than ever before, but are we losing perspective on what that quality of life looks like? I am convinced that we are too quick to assign the loss of physical capacity to aging and other factors outside of our control. While John’s observation may be aimed at the able-bodied population, the message, as it relates to the importance of healthy muscle and movement, is also relevant for the O&P patients we treat.

While I have learned many lessons over the course of my residency, the one that stands out the most in shaping my outlook on patient care came from outside O&P. Dan John, a strength and track and field coach, said, “The older population is a window to us all.” As a society, we are living longer than ever before, but are we losing perspective on what that quality of life looks like? I am convinced that we are too quick to assign the loss of physical capacity to aging and other factors outside of our control. While John’s observation may be aimed at the able-bodied population, the message, as it relates to the importance of healthy muscle and movement, is also relevant for the O&P patients we treat.

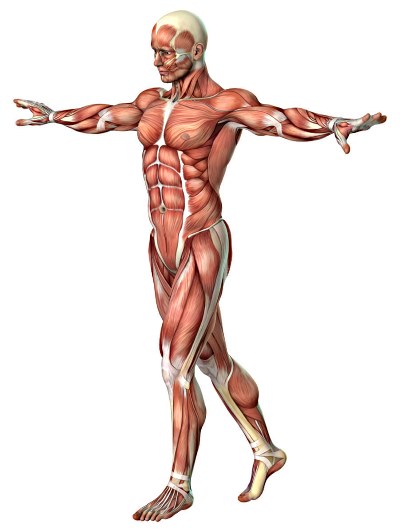

Human beings were built to run, jump, push, pull, squat, hinge, and carry; these are basic human movements, but they become compromised with age. When is the last time you ran a distance, picked up something heavy, or just played on a playground? As we age, movement becomes less generalized and more specific; we sit for long periods and lack variety of movement. Overdeveloped anterior musculature and neglected posterior musculature have produced a push-centric society. These adaptations characterize the crouched body posture of old age. This is the same posture we see in people who are chronically detrained and in much of the O&P patient population. A deeper understanding of kinesthetic development and muscular adaptation enables us to identify and address areas of concern before they become catastrophic failures. Patients should not accept that low levels of function are natural or to be expected based on age, pathology, or impairment.

Muscle and movement are immeasurably important to function, health, and quality of life. Research has proven that sarcopenia, age-related muscle wasting, is responsible for a 3-8 percent muscle mass loss every decade after the age of 30, and the effects of aging are compounded by lifestyle and neglect.1 We have become a culture of non-movers. As few as two weeks of complete physical inactivity can have the same effect on muscle loss as a decade of aging.1 So, is getting older the issue, or do we lack an understanding of how important muscle and movement truly are?

Muscle plays many critical roles in overall health. It regulates body temperature and fluid flow, and it is vital to metabolic efficiency. Muscle is the metabolic powerhouse of the body; it provides a landscape of insulin receptors, a sink for energy storage, a depot of amino acids, and it is a secretor of cytokines.2 Strong muscles increase spontaneous activity levels, decrease our reliance on others, and enable us to live longer, healthier, higher-quality lives. Healthcare professionals must emphasize the importance of building and maintaining high-quality muscle to all patients.

Healthy muscle drives human movement, and movement keeps us strong and vital. Our goal as practitioners cannot be just to generate better movers. The goal must be to advocate for all movement, to improve function, and to get the patient moving without sacrificing future movement. There is a difference between moving and moving well, but there is no bad physical activity. It is easy to go down the rabbit hole, searching for perfection with a goal of symmetry and decreased energy expenditure. But if you sacrifice function, then you are missing the point. The clinical decisions healthcare professionals make have physical consequences for patients. Everybody presents with a different set of limitations, compensations, and considerations. The O&P professionals’ unique understanding of human biomechanics, functional anatomy, and pathology allows them to work within these boundaries to provide patients with a device that prioritizes function, optimizes performance, and prevents further adversity.

The importance of healthy muscle and quality movement cannot be overstated. Healthy muscle keeps us standing upright, drives human movement, and primes metabolic function. Movement is not just how we interact with the world; movement lubricates the body and preserves muscle quality. Movement is standing up from a seated position, walking your dog, or picking up your grandchild. There is no barrier to entry for increasing movement or physical activity. As practitioners, it is our responsibility to provide patients with the information they need to be successful with their O&P devices. We can teach our patients how to self-evaluate and quantify their movements by asking questions to guide them, such as, “How often are you standing versus sitting?” “What does your non-exercise physical activity level look like?”

During one of the first weeks of my residency, I shadowed a practitioner who was consulting with a patient who has Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease. The patient complained of poor balance, back pain, difficulty walking, and difficulty participating in activities that he once enjoyed. I asked him what a normal day looked like (non-exercise movement practice). He told me he spent a lot of time sitting. I asked him if he exercised. He said that he used to swim. I told him that swimming was great and suggested he resume that activity. I told him the body is an adaptation machine and that it operates under the use-it-or-lose-it directive. Before he left, we talked a little more about what he was passionate about and why movement is important. We discussed posture and the difference between flexibility and mobility. I saw that patient in our office over a year later and he told me that talk changed his life; he was stronger, was in less pain, was enjoying outdoor activities, and had “way more energy.”

That moment provided clarity for me. Out of all the healthcare professionals that he had seen, no one had suggested that he should move more or that poor posture might be an aggravating factor for his complaints. Just because people have been standing, walking, and breathing their whole lives doesn’t mean they are experts. By doing these tasks poorly, they are reinforcing poor habits and digging a deeper hole for themselves. Quantity does not trump quality. The human body is a smart system; when it is active and in a good position, it works well. Small changes are the easiest to make and offering simple coaching cues to patients can have a profound impact. By providing basic points of reference, you can help your patients move more and move better. Teach, talk, and discuss.

If a patient’s leg does not function well, discuss how it should function. Take the time to talk with the patient, answer questions, and provide information. Providing understanding equips patients with the tools to be successful and empowers patients to take ownership of their health. Explain how you are going to work together to improve their functionality. It is our responsibility as healthcare professionals to educate our patients, help them understand their bodies, and become competent movers.

John Pope, MS, MPO, CSCS, is a resident at Orthopedic Appliance Company, headquartered in Asheville, North Carolina

References

1. “Muscle Matters: Dr Brendan Egan at TEDxUCD.” YouTube video, 13:57. Posted by TEDx Talks, June 27, 2014. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LkXwfTsqQgQ

2. Sullivan, J., and A. Baker. 2016. Barbell Prescription. Wichita Falls, TX: The Aasgaard Company.

3. Johns Hopkins Medicine. “Risks of Physical Inactivity.” (n.d.). Retrieved June 20, 2017, http://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/healthlibrary/conditions/cardiovascular_diseases/risks_of_physical_inactivity_85,P00218/