Abstract

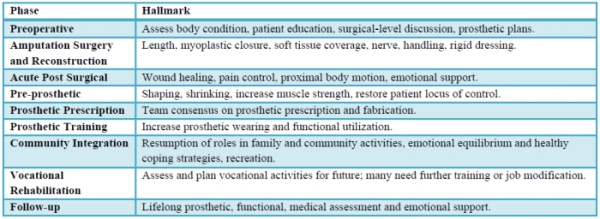

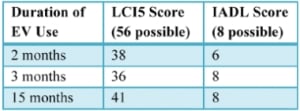

The process of functional development with a prosthesis is vital to a patient’s overall health and quality of life, but very few studies exist that track long-term functional development. As the O&P profession moves toward evidence-based practice, the need for clinically valuable research about patient function becomes more important. In this report, a clinical researcher used two standard functional assessments to track one patient’s development through prosthetic training and community integration, as well as the follow-up stages of rehabilitation. The patient is a 74-year-old, non-diabetic male with a transtibial amputation. Data collection began after the patient started using an elevated vacuum (EV) prosthesis. Assessments included the Locomotor Capabilities Index-5 (LCI5) and the Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADL) index. Four months after amputation, the patient received average scores on both assessments. During the final appointment, the patient was well above average compared to similarly aged amputees.

Introduction

The goals of prosthetic rehabilitation are to improve the new amputee’s functional capability and to successfully reintegrate the patient into his or her community. Function can affect more than just mobility; in a study of 25 transtibial and transfemoral amputees, Deans et al. found that there was a significant relationship between amputees’ functional ability and their physical, psychological, and social well-being.1 While there are many advanced technologies that claim to improve patient function, the research is often inadequate in terms of experimental design and ecological validity.2 In fact, a national meeting to assess the research needs in O&P cited outcomes research as the highest ranked area of need.3 To help fill this need, a prosthetist or physical therapist can perform quantitative functional assessments to gauge the effectiveness of various interventions and components with an individual patient. A previous case report showed how these types of assessments were used to quantify the impact of prosthetic knee choice on balance confidence.4 This allows the prosthetist to see which components have the most positive impact on the patient’s function, and, by extension, his or her successful reintegration into the community.

However, very little has been studied about functional development after major limb amputation. Munin et al. studied the predictive factors for early ambulation among lower-limb amputees but ended data collection after the patients were discharged from inpatient rehabilitation.5 The results showed that early prosthetic training can be beneficial in the short term; however, long-term effects were not considered. Another study assessed the functional abilities of transtibial amputees one year after amputation, and those results were used to show that longer residual limbs can be associated with improved mobility.6 While valuable for comparison, a cross-sectional study like this one does not consider the way in which the patients reached independence, nor does it include the components used by each patient. A study showing how similar patients progress functionally through the prosthetic process would be more valuable to a prosthetist. Furthermore, while research on patient function following amputation exists, the outcome measures used are standard gait protocols with limited ecological validity to assess community mobility.2 Therefore, valid, quantitative research is needed to illustrate how a patient progresses through the recovery process.

Each phase of amputee rehabilitation has distinct challenges, goals, and outcomes (Table 1). This case study reports on the functional development of one patient from prosthetic training to follow-up, assessing his functional status at various intervals.

Case Presentation

The patient is a non-diabetic 74-year-old male. He is six feet tall and weighs 143 pounds. After a postoperative blood clot led to gangrene in January 2010, the patient underwent a right transtibial amputation. No other vascular symptoms have been reported. He is osteoporotic and underwent a total knee replacement on his left knee in 1999 and on his right knee in 2001. He smokes three small cigars daily and does not drink alcohol. He is retired and lives in a two-story home with his wife but does not use stairs daily. Prior to the amputation, he required no assistive devices to ambulate independently and enjoyed camping and yard work.

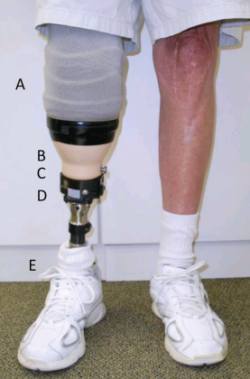

The patient is being treated by a prosthetist and physical therapist at Dayton Artificial Limb, Ohio. He received a patellar-tendon-bearing (PTB) socket in March 2010, but immediately experienced sharp pain at distal patella and distal tibial prominence accompanied by persistent redness in those areas. The prosthetist added dense pads to the patellar region and distal end of the socket, but the patient experienced little improvement. The clinician and physical therapist agreed that the patient was a good candidate for an EV system because it could relieve the areas of high pressure on the patient’s residual limb by evenly distributing forces over a total-surface, weight bearing socket.7 He began wearing the EV prosthesis (Figure 1) in May 2010, and the clinician evaluated his functional status at the two-, three-, and 15-month landmarks in the training and community-integration stages of his rehabilitation process.

Assessments

The patient completed two assessments as a part of this study. The first assessment was the LCI5, a measure of a lower-limb amputee’s self-reported perceived capabilities with a prosthesis. It was originally developed as part of the prosthetic profile of the amputee questionnaire and consists of 14 basic and advanced activities on a five-point ordinal scale. The LCI5 demonstrates good internal consistency, test-retest reliability, and construct validity when used with adults with lower-limb amputation.9-11 It has been shown to be able to detect changes in functional limitations throughout rehabilitation,6,11 making it appropriate for this report.

The second assessment was the IADL index, which is used to measure functional independence in a wide range of patient groups.12 While not a measure of locomotor ability, it does yield information about a patient’s general ability to perform daily tasks. It is especially useful for this patient because the researcher hoped to compare the patient’s performance to non-amputees in his age group, and age-matched norms are well established for IADL. Both assessments were given in an interview so that the clinician could clarify any questions the patient had about the measures.

Outcome

Table 2: Patient’s Functional Assessment Results

Two months after receiving the vacuum prosthesis, the patient completed the LCI5 and IADL assessments (Table 2). While adjusting to his vacuum prosthesis and using a cane, he scored 24 points in general activities and 16 points in advanced tasks. His IADL score reflects an inability to do light housekeeping tasks.

After three months of wearing the prosthesis, the

patient came into the clinic for a routine prosthesis check and functional evaluation. He still walked with the assistance of a cane and expected to continue doing so. He reported that sometimes he doffs the prosthesis if his residual limb begins to ache within the first 20 minutes of donning, but he usually re-dons it after his residuum “calms down.” From that point, he wears the prosthesis for four to six hours without pain. The redness he experienced with the PTB socket had largely disappeared, and his limb appeared healthy, even showing hair re-growth at the distal end (Figure 2). Again, the clinician administered the LCI5 and IADL assessments. His LCI5 score decreased for two advanced tasks: going up a few stairs without a handrail and walking while carrying an object. He indicated that he would only perform those tasks if someone was nearby. His IADL score improved because he felt more confident performing light household work like putting away dishes. No major component changes were initiated because the patient’s progress seemed to be adequate with current components.

At the 15-month follow-up appointment, the patient said that he still occasionally needed to doff the prosthesis shortly after donning if it felt unbearably tight. He usually re-donned the prosthesis after 30 minutes. The patient had experienced pain around the medial and lateral femoral condyles of his affected side, so the prosthetist attempted to relieve some of the pressure around those areas with relief cutouts on the patient’s outer, rigid socket (Figure 5). The patient felt an improvement in fit and expressed no increased instability.

Functionally, the patient has improved significantly in the 12 months since the second evaluation. He said that he is able to perform the majority of the tasks on the LCI5 either unaided or alone with a cane. Qualitatively, he said that he is unable to camp, a hobby that he had enjoyed before the amputation. However, the patient is excited about an upcoming family reunion where he will be responsible for grilling enough food for 40 people. He also is able to maintain one acre of land weekly using a tractor.

Discussion

While this patient’s quantitative functional growth did not show improvement between the two- and three-month appointments, the health of his residual limb improved dramatically when compared to its condition with the PTB socket system. Hair regrowth was unexpected and has not been officially documented, but the prosthetist suspects that it is due to reduced vertical movement in the prosthetic socket during gait, a phenomenon that has been recently shown with vacuum patients.13,14 Similarly, the decrease in redness of the limb that the patient experienced with the use of the vacuum prosthesis was likely due to even distribution of force in the total-surface, weight bearing socket compared to the PTB version.

Support authors and subscribe to content

This is premium stuff. Subscribe to read the entire article.